The fashion industry uses quite a lot of chemicals for clothing manufacturing. After all, there’s a lot that’s required to transform something from raw materials (whether it’s cotton plants or fossil fuels) into a colorful t-shirt or a durable pair of jeans. Not only is there weaving and spinning, dyeing and printing, but there are also a bunch of other things commonly added to textiles to make the color last, to make fabrics “wrinkle-free,” to make them water-resistant, to make them stretchy… You get the idea.

Unfortunately, much like the beauty and personal care industry, there is little legislation or accountability when it comes to the hazardous chemicals used by the fashion industry. As you’ll see, the chemicals in clothes have the potential to cause or contribute to everything from skin irritation and contact dermatitis, to reproductive system damage and birth defects, to cancer, and more.

When these chemicals are released into our air and waterways, they can not only affect human health but also that of wildlife and ecosystems at large.

This can be quite alarming, considering we wear clothes against our skin all day long. However, this guide is not meant to try and convince you to throw everything out of your closet and do a wardrobe overhaul overnight. That would be stressful, expensive, and unrealistic.

Rather, the hope is that after reading this article, you will have a more thorough understanding of the toxic chemicals found in clothing so that you can:

- a) take small steps towards a non-toxic wardrobe (we’ve included many action steps you can take below)

- b) consider pressuring your representatives to enact legislation that would prohibit these chemicals in manufacturing (so that it’s not all up to the consumer)

Table of Contents

- How Do Harmful Chemicals Get Into Our Clothes?

- 14 Toxic Substances That May Be In Your Clothing

- 1. Formaldehyde

- 2. PFAS

- 3. Azo Dyes

- 4. BPA

- 5. Phthalates

- 6. PVC

- 7. Pesticides

- 8. Lead

- 9. Antimony Compounds

- 10. Other Heavy Metals

- 11. Nonylphenol Ethoxylates

- 12. Nanoparticles

- 13. Flame Retardants

- 14. TDI and MDI

- 15. Antimicrobials

- BONUS: Perc (dry cleaning)

- Ways to Minimize the Toxic Chemicals in Your Wardrobe

- Where to Find Non-Toxic Clothing Brands

How Do Harmful Chemicals Get Into Our Clothes?

Before we get into the specific chemicals, there are two points to keep in mind when it comes to toxic clothing:

Raw Fabrics vs. Finishes

Some fabrics are more toxic than others (for example: polyester versus organic cotton). However, it also matters what goes on that fabric before it hits the shelves. For example, an organic cotton jacket (which was grown without toxic pesticides) may be treated with a toxic PFAS-laden finish to make it water-resistant.

This is where third-party certifications can be helpful. For example, OEKO-TEX certifies that a finished product is free from a variety of toxic chemicals. GOTS certifies both semi-finished and finished products, so if you see a GOTS label, you may need to clarify which part(s) of the product is certified.

Intentionally-Added Chemicals vs. Contaminants

The next thing to keep in mind is that sometimes chemicals are added intentionally and other times they are present in clothing as a result of contamination.

For example, lead may be present in a cotton t-shirt because there was lead in the soil the cotton was grown in (an example of contamination), or if may have been used as a color-stabilizer in the dyeing process (intentional).

Or to use another example, PFAS may be added to make clothing water- or stain-resistant (intentional) or if may have worn off onto the clothing from the machinery used to make the garments (contamination). (Recent US legislation has started banning intentionally-added PFAS, so that likely won’t be as much of a problem in the next several years!)

While manufacturers should do what they can to eliminate contamination, the intentionally-added toxics are generally a bigger problem simply because they’re going to end up in our clothing (and soil, air, and waterways) in much larger concentrations.

Related:

Home

Best PFAS-Free Clothes Steamers and Irons

Believe it or not, toxic PFAS chemicals could be on your iron. I spent over 10 hours calling and emailing brands to find out which steam irons are non-toxic and PFAS-free.

14 Toxic Substances That May Be In Your Clothing

Now let’s talk about the different toxicants that may be lurking in your wardrobe…

1. Formaldehyde

If you’ve ever pulled an article of clothing out of a box and experienced a strong “chemical” smell, there’s a good chance that’s formaldehyde. Formaldehyde is often used in various kinds of textiles for a variety of reasons, such as:

- To prevent/decrease wrinkling.

- To prevent shrinking (especially for cotton-polyester and wool-polyester blends, which have a higher tendency for shrinkage).

- To prevent static cling.

- To prevent mold, mildew, and bacteria growth during shipping.

- To increase stain resistance.

- To hold shapes and colors.

Although formaldehyde is a naturally-occurring substance, the amount in our environments have reached toxic levels. Formaldehyde is all over the place: in our furniture, glues, paints, insulation, as well as cosmetics and personal care products. It’s also released into the air via industrial manufacturing.

Formaldehyde is a known carcinogen. It can also cause acute reactions, especially in people who are more sensitive. This can include things like lightheadedness; skin rashes, itching or burning; watery or red eyes; burning in the throat; or coughing.

Many countries have laws regulating formaldehyde in textiles, but the U.S. unfortunately isn’t one of them. There have been various lawsuits over the last few decades over formaldehyde in clothing, including Victoria’s Secret bras and Delta Airlines uniforms.

Formaldehyde is a volatile organic compound (VOC), meaning it can vaporize into the air at room temperatures (and above). This means that simply wearing clothes or sleeping on sheets that contain formaldehyde could potentially release formaldehyde into the air around you as your body heats up the fabric.

What you can do:

- Try to avoid clothing and textiles with labels like “wrinkle-resistant,” “easy care,” “permanent press,” “iron-free,” “anti-cling,” “stain-resistant,” “moth-proof,” and “color-fast.”

- Wash your clothes before wearing them. (This likely won’t get rid of all of the formaldehyde that may be there, but it may get rid of some of it.)

- For baby products, look for the OEKO-TEX certification. (Baby products fall under OEKO-TEX’s Class 1, which prohibits formaldehyde. Classes 2-4, which include other items like underwear and outerwear, allow formaldehyde in varying degrees.)

- Look for GOTS certified clothing. (GOTS does allow for a certain amount of formaldehyde to account for contamination, but it does not allow for added formaldehyde.)

2. PFAS

Most people are at least somewhat aware of PFAS (also called PFCs or “forever chemicals”) chemicals these days, as they’re in the news quite a bit. These are the “Teflon” chemicals that make fabrics water-resistant. They’re commonly added to things like raincoats and boots, and you’ll also find them in other water-resistant polyester textiles, like camping tents.

The U.S. EPA has said that there is no safe level of at least a few types of PFAS. There are all kinds of negative health effects associated with PFAS exposure, including cancer, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, thyroid dysfunction, ulcerative colitis, immune deficiencies, and more.

They are persistent chemicals, which means they don’t break down. Instead, they just build up in our environment and in our bodies over time. (This is one of the reasons why they’re especially concerning.)

What you can do:

- Try to avoid “water-resistant,” “water-proof,” or “stain-resistant” clothing when possible.

- Look for waterproof gear from brands that are using PFAS alternatives.

- Wait it out! Legislation in states like California and New York have begun banning intentionally-added PFAS in clothing. Brands like REI, Patagonia, Ralph Lauren, Abercrombie & Fitch, and others have committed to phasing out PFAS over the next several years. So by 2026-ish, there should be significantly less PFAS in our clothing, even water-resistant products like raincoats.

3. Azo Dyes

Azobenzene dyes (more commonly known as just “azo dyes”) are very commonly used to create vibrant colors (like bright blues and greens) as well as dark colors (like black). Many sources state that anywhere from 50 to 80 percent of fabric colorants use azos (although, we haven’t been able to find the original source of those estimates).

Sometimes, the azo dyes themselves are carcinogenic. But other times, their metabolites—called aromatic amines—are carcinogenic. They can also potentially cause an adverse skin reaction, especially in those who are predisposed to things like sensitive skin, eczema, and allergies.

Some of these dyes are water-soluble, which means your clothes may become more toxic when you sweat in them. (That also means they’re polluting waterways around the world.)

The European Union has banned many azo dyes and aromatic compounds, and California has also added them to the Prop 65 list, which means that clothing sold to California residents that contains azo dyes should come with a warning label. However, it seems there may not be a lot of enforcement on these bans and warnings since amines have still been found in some garments.

What you can do:

- Look for GOTS and OEKO-TEX certifications, which prohibit azo dyes.

- Avoid fast fashion reatilers when possible, as they’re more likely to use azo dyes.

- Buy from brands that use plant-based dyes.

- Opt for undyed garments.

- Wash your clothing before you wear it.

- If possible, don’t let sweaty clothing sit on your skin for too long.

4. BPA

Many people are aware of bisphenol A (aka BPA). It’s mostly associated with plastic products like water bottles, baby bottles, and food storage containers… But recent testing has revealed BPA in clothing as well.

The Center for Environmental Health (CEH) began testing socks for BPA in late 2021 and “found over 100 brands of socks that tested over California’s safe limit for exposure” to BPA (some as high as 31 times the legal limit under CA law). The socks they tested were for babies, children, and adults, and they came from a variety of brands, including Hanes, Gap, Timberland, Reebok, and more.

They tested socks with a variety of different blends, including polyester, cotton, and spandex. They found BPA in the socks made from polyester and spandex and did not find BPA in the socks made predominantly out of cotton. It might make sense that BPA would be more likely found in polyester fabrics since polyester is a petroleum-based plastic material.

Then in 2022, the CEH tested another category of clothing: sports bras and athletic shirts. This time, they found that the clothing they tested “could expose individuals to up to 22 times the safe limit of” BPA allowed by CA law. Brands included Athleta, PINK, The North Face, Nike, Reebok, and more.

Again, the clothing that was found to have BPA were those made primarily out of polyester and spandex.

BPA is a known endocrine disruptor and has been linked to developmental harm, cancer, heart disease, anxiety, depression, hyperactivity, and more. One of the more concerning aspects about BPA is that it’s been found to have negative effects even at very low levels, defying the classic belief that “the dose makes the poison.”

It’s known that BPA can be absorbed through the skin via contact with BPA-laden paper receipts, so it’s reasonable to assume that BPA may also be absorbed through the skin through contact with clothing and other textiles as well.

What you can do:

- When possible, buy socks (and underwear and other clothing) made primarily of natural materials such as cotton, organic cotton, or wool.

- Look for the bluesign® certification, which limits BPA in textiles.

- When you buy new activewear, look for brands that are plastic-free or almost plastic-free.

- If and when you do wear synthetic socks, activewear, or other clothing, try to minimize the amount of time you spend in them. For example, you may choose to wear synthetic clothing during your workout but then remove them when you’re finished exercising and switch to natural and organic fabrics for the rest of your day and night.

5. Phthalates

Like BPA, phthalates are known endocrine disruptors that are commonly used in plastic products. They are found in PVC clothing and accessories, but it’s also used in the printing process (to soften inks), as well as for those plastic-y labels and graphics on t-shirts (like cartoon characters or sports team logos).

There have been a few investigations in recent years that have found elevated levels of phthalates in jeans, raincoats, vegan leather, and other clothing items. Brands found to contain phthalates have included Shein, Zara, Calvin Klein, and others. One 2021 investigation even found phthalates in several children’s products, including a children’s tutu and a purse from Shein, and a Frozen dress and kids’ raincoat from AliExpress. Alarmingly, they’ve even been found in infant cotton clothing.

Phthalates are linked to a wide variety of health concerns, including reproductive problems, type II diabetes, cancer, high blood pressure, delayed neurodevelopment, and even allergies and asthma.

What you can do:

- Avoid PVC clothing and accessories.

- Incorporate more undyed clothing into your wardrobe, especially for things like pajamas and baby clothes. A few brands that offer undyed clothing include Harvest & Mill, Danu, Bébénca, Industry of All Nations, Rawganique, and TOY.

- Look for OEKO-TEX and bluesign® certified textiles. Phthalates are not outright banned by these third-party labels, but there are limits to the types and levels of phthalates allowed.

6. PVC

PVC is one of the most toxic kinds of plastic. It’s made using toxic chemicals such as vinyl chloride (the main chemical released in the East Palestine train derailment), ethylene dichloride, heavy metals, and phthalates, and it creates carcinogenic byproducts like dioxins.

It’s relatively easy to identify PVC in your wardrobe because it’s so plastic-y. It’s used to make things like raincoats, rain boots, vegan leather, and clear bags, and shoe straps.

What you can do:

- Choose alternatives when you can. For example, look for rain boots that are made from natural rubber and rain jackets made from safer synthetic fabrics such as nylon.

- For instances when you need a clear bag for security reasons (such as concerts and sporting events), go for a mesh one instead, like this one. It’s made from polyester, which is not the best material, but it’s better than PVC. Or you could use an organic cotton mesh market bag, like this one.

- If you do have PVC products, try to keep them out of the heat to reduce chemical leaching into the air.

7. Pesticides

There are two main ways pesticides can potentially get into your textiles: either through the growing process of the fiber itself (for example, glyphosate sprayed onto the cotton used to make a t-shirt), or pesticides can be sprayed onto the finished product in order to prevent damage from pests during transport.

After polyester, cotton is the most widely used textile globally. According to a 2007 report from the Environmental Justice Foundation and the Pesticide Action Network UK, “Cotton accounts for 16% of global insecticide releases—more than any other single crop.”

There is a wide range of toxic pesticides used on cotton, many of which have been classified as extremely or moderately hazardous and/or carcinogenic by agencies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the IARC.

It’s unclear if there are any pesticides left in a finished piece of cotton clothing or bedding (and if so, how much). So the main issue here is not so much about the specific piece of clothing against your skin, but rather the impact of pesticides on the ecosystem as a whole.

Pesticides pose health risks for the farmworkers and community members (including children) who are directly exposed… But then the rest of the world is also exposed as those pesticides work their way into our soil, the food we eat, and the water we drink and bathe in.

The potential health effects of pesticides on humans are wide-ranging, from acute effects like nausea or respiratory problems, to chronic conditions such as cancer and mental disorders. Our heavy use of pesticides is also harming wildlife (including bees) and plant biodiversity as well.

Besides cotton, other natural fibers such as linen and hemp can technically still be grown or processed using pesticides, but it’s much less likely because these types of crops just don’t tend to need as many pesticides to thrive.

Unfortunately, it’s nearly impossible to know if finished clothing has been sprayed with pesticides for shipping (unless you actually test it in a lab). Clothing that comes from overseas and is therefore in transport for a long period of time may be more likely to be sprayed. Therefore, buying from brands which have localized production as much as possible may be a good idea.

For example, Harvest & Mill’s entire supply chain—from the cotton seed to the finished product—takes place in the U.S. Not only does this give them more control over the supply chain as a whole, but it also eliminates any need to spray toxic pesticides on their clothing to ship it overseas.

What you can do:

- Buy from brands that use organic cotton and/or other natural fibers such as hemp, linen, and wool when possible.

- Look for third party organic certifications, which can help provide a specific set of standards and a certain degree of accountability for brands. These include things like Organic Exchange (OE) and Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS).

- Buy from brands that localize their supply chains as much as possible.

8. Lead

Most people are aware that lead is toxic, even at low levels. It can cause damage to the brain, heart, kidneys, and reproductive system.

It can technically be found in natural fibers like cotton since plants can draw lead up from the soil. However, it’s moreso found in higher amounts when it’s added intentionally as a part of the manufacturing process. One of the more common reasons it’s used is to stabilize the dye for brightly colored clothing.

A 2021 Marketplace investigation found lead in several different products, including a Shein jacket made for toddlers that “contained almost 20 times the amount of lead that Health Canada says is safe for children.”

Excess levels of lead have also been found in products from Urban Outfitters, Charlotte Russe, and Forever 21, along with kids’ Disney clothing that was sold at places like TJMaxx and Amazon.

What you can do:

- Opt for undyed clothing or clothing that has more muted and neutral colors (especially for babies and children)

- Look for OEKO-TEX, GOTS, and bluesign® certifications, all of which have limits to the amount of lead and other heavy metals allowed in products.

- Avoid fast fashion, as it seems to be more likely to contain lead.

9. Antimony Compounds

Antimony is a heavy metal used to produce polyester and other PET plastic products. It’s used as a catalyst in the making of the plastic material itself, as well as in the fabric dyeing process.

Short-term effects to antimony via inhalation can include skin and eye irritation, while longterm effects can include inflammation of the lungs, chronic bronchitis, chronic emphysema, and more. These effects are most likely to be experienced by industrial workers who are exposed to higher levels of antimony, rather than the end consumer wearing polyester clothes.

Trivalent antimony is commonly used to make flame retardants, which are added to clothing and pajamas. Trivalent antimony classified as probably carcinogenic to humans by the International Associations for Research on Cancer (IARC) and it’s on California’s Prop 65 list. Some research also suggests that trivalent antimony may contribute to the endocrine disrupting effects of polyester.

Antimony can be found in the final textile product, but research shows that washing your clothing before using or wearing it for the first time can help decrease your exposure.

The good news here is that chemical flame retardants in things like children’s pajamas are no longer required by law in the US, and some states have even banned them in children’s products. (More on this below.) That doesn’t mean you won’t still find fabrics that have been treated with flame retardants, but it does mean it’s easier to find flame-retardant-free clothing than it was at one time.

What you can do:

- Wash your clothes before wearing them for them first time.

- Buy clothing from brands that do not use flame retardant chemicals.

- Look for OEKO-TEX, GOTS, and bluesign® certifications, which limit the amount of antimony and other heavy metals that are allowed in products.

10. Other Heavy Metals

In addition to lead and antimony, there are other heavy metals of concern in clothing as well.

Chromium VI, or hexavalent chromium (also known as the Erin Brockovich chemical) is probably most well known for its use in leather tanning. But like a lot of the other toxic chemicals on this list, it can also be used in the dyeing process for other types of fabrics.

It is recognized as a carcinogen by the National Toxicology Program and labeled as carcinogenic to humans by the IARC.

Even though chromium VI may be the most common one, it isn’t the only toxic chemical used in leather tanning. In fact, there are a lot of harsh chemicals that may be used, including formaldehyde; coal tar; sulfuric acid; ammonia; PCBs; other heavy metals like antimony, mercury, and arsenic; and more. While it’s unclear how much of these chemicals are left in final products, there’s no doubt that they are polluting our global water supplies and poisoning communities around leather production facilities.

What you can do:

- For leather clothing and accessories, look for vegetable-tanned/chrome-free leather.

- Look for Leather Working Group certified leather, which aligns with Afirm and ZDHC chemical management targets. (Heavy metals are not prohibited, but they are limited.)

- Opt for more undyed clothing throughout your wardrobe.

- Look for OEKO-TEX, GOTS, and bluesign® certifications, all of which limit the amount of heavy metals allowed.

11. Nonylphenol Ethoxylates

Nonylphenol ethoxylates, also called NPEs or NPEOs, are a class of ingredients that are commonly used throughout the manufacturing process. (They’re part of an even larger class of substances called Alkylphenol, or AP, and Alkylphenol Ethoxylates, or APEOs.)

NPEs are used as surfactants or emulsifiers in industrial detergents, but they’re also used for things like dispersing dyes, printing patterns, spinning yarn, scouring leather and wool, softening fabrics, and more.

NPEs are endocrine disrupting chemicals that have been found to cause various reproductive and developmental problems in humans, fish, and mice. They’re also bioaccumulative, which means they don’t biodegrade very quickly and can build up in the environment over time, working their way through the entire food chain.

NPEs can end up in finished clothing. In 2012, Greenpeace tested 78 garments that were purchased from around the world and found that two-thirds (52) of them tested positive for NPEs at concentrations above the limit of detection (1 mg/kg). Levels ranged widely, from just above 1 mg/kg all the way to 1100 mg/kg.

A few years after that report was released, the E.U. banned NPEs from textile imports. (NPEs had already been banned in clothing produced inside the E.U.) Although there are no NPE restrictions in the US, it does fall under the Significant New Use Rule (SNUR), which means that companies must notify the EPA if they start using these chemicals in new ways.

It’s also worth noting that some research has shown that when nonylphenol is combined with BPA, “the combined effects of the chemical mixture might be stronger than the additive values of individual chemicals combined.”

What you can do:

- Wash your clothing and textiles before you wear them.

- Buy OEKO-TEX and/or GOTS certified clothing. Both of these certifications prohibit the use of NPEs.

- For big brands (like Nike and Adidas), look for companies that are members of Afirm or ZDHC. Afirm prohibits APEOs but allows for trace amounts that result from contamination. APEOs are also on ZDHC’s Restricted Substances List (although they’ve found that brands commonly exceed acceptable levels.)

- Buy clothing from EU-based brands.

12. Nanoparticles

This is a somewhat controversial one, in part because the technology is relatively new and there’s not a lot of research on it yet.

Some clothing manufacturers have started weaving nanoparticles (which are defined as being within 1-100 nanometers in size) into fabrics to give them certain performance qualities.

The most common types are nanosilver, which is added to fabrics to give them antibacterial properties, and nano-titanium dioxide, which adds sun protection to clothing.

A big part of the problem is that a lot of the potential negative effects of nanotechnology depends on just how nano it is. For example, is it small enough to pass through the blood-brain barrier, or into the organs? Basically, different sizes may have different effects on the body.

One study showed that 20 nm nanosilver particles can enter human cells and cause the development of cell-damaging free radicals. (Overproduction of free radicals are associated with a number of chronic health concerns, including cancer, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s.)

There’s also the question or whether or not more use of antibacterial silver will contribute to the rise in antibiotic resistance and decrease silver’s antibacterial abilities over time. As it washes out of our clothes and into our soil and waterways, it could potentially disrupt the ecosystem’s microbiome as well, causing trouble for plants, fish, and other wildlife.

Research into nanotechnology hasn’t kept up with the rise in nanotech in the consumer market (and manufacturers are not required to prove their product is safe before selling it). So if you prefer to take the precautionary principle when you can, you might want to opt out of wearing clothes that contain nanoparticles. It’s relatively easy to keep this kind of clothing out of your wardrobe.

What you can do:

- Opt out of clothing made with nanosilver or nano-titanium dioxide.

- When a garment is advertised as “anti-microbial,” “anti-bacterial,” “odor-resistant,” or “UV-resistant,” check to see what exactly gives it those properties. (Certain natural fabrics such as hemp are naturally antimicrobial.) Don’t be afraid to reach out to the company and ask for more details.

13. Flame Retardants

There is some good news here! You actually don’t need to worry too much about fire retardants in clothing as much as you used to. (With the exception, of course, being clothing that’s specifically meant to withstand fires, such as firefighting and military gear.)

The main concern with flame retardants in clothing has had to do with children’s pajamas. Back in the early 1970s, the U.S. enacted legislation that required children’s pajamas to be fire resistant.

But it wasn’t too many years later that scientists like Dr. Arlene Blum sounded the alarm on these chemicals—specifically, a brominated flame retardant called Tris(2,3-dibromopropyl) phosphate (also known as “Tris” or TDCPP for short). Tris is linked to a variety of serious health concerns, including cancer, DNA mutation, and negative reproductive effects.

In the late ’70s, the federal Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) prohibited the use of Tris in children’s pajamas. Even though the courts struck down the ban, manufacturers saw the writing on the wall and (mostly) removed it from their PJs anyway. They did the same for a related compound called chlorinated Tris, even though that one was not officially banned either.

Children’s pajamas are still required to meet flame resistant standards, but they can do so by simply being tight-fitting (since loose clothing is more likely to catch fire). Look for a tag or label on your kids’ pajamas that says something like:

Not Flame Resistant. Should Fit Snugly: For children’s safety, garment should fit snugly. This garment is not flame resistant. Loose fitting garment is more likely to catch fire.

It may be worth noting here that flame retardants are still used in other products, such as furniture and electronics. If you’re interested in taking a deep dive into the issue of flame retardant chemicals, how they got into consumer goods, and how they don’t actually even work, check out the documentary Toxic Hot Seat or the Chicago Tribune series “Playing With Fire.“

What you can do:

- Buy children’s pajamas that are fit snuggly. Look for the label that says “Not Flame Resistant.”

- Look for the OEKO-TEX certification. Although OEKO-TEX does not completely ban flame retardants, they have banned the most toxic ones. OEKO-TEX states that all of the “approved” flame retardants chemicals have been evaluated by partner toxicologists and that they reserve the right to remove approved chemicals in the future “if new scientific findings come to light which question the safety of a substance with regard to health.”

- Shop at Target. Target set a goal of removing all added flame retardants from clothing by 2022. It’s not clear at this point if they hit that goal, but we will update this guide as soon as we find out. (You can also use Retailer Report Card to see how other stores rank on flame retardants and other chemicals.)

14. TDI and MDI

Toluene-2,4-diisocyanate and Methylene bisphenyl-4,4-diiisocyanate, also known as TDI and MDI, are precursors of the polyurethane used to make spandex.

TDI is an acute and chronic toxicant. Acutely, it can cause irritation of the skin, eyes, respiratory tract, GI tract, and central nervous system. Due to its ability to cause cancer in animal studies, it’s classified by the IARC as a possible human carcinogen.

MDI can also cause acute problems such as dermatitis, eczema, and eye irritation, but it has not shown to be carcinogenic to date.

TDI and MDI are also used for other types of products like paints glues, and PU foams.

You should actually have to worry about TDI/MDI in your spandex because manufacturers are subject to quality control measures to ensure that no residual TDI or MDI exists in the final product.

That being said, it’s suspected that these chemicals may be at least partly to blame for spandex allergies. If you are experiencing a negative reaction to clothing (like itchy, red skin), you may want to try taking all spandex out of your wardrobe for a month or so and see if it makes a difference.

15. Antimicrobials

Clothing, textiles, and other products that are treated with antimicrobials and antibacterials have become very common. Labels like “germ-resistant,” “anti-odor,” and “washless” indicate that antimicrobials may have been added.

Some of these antimicrobials are worse than others. Many of them contribute to antibiotic resistance, which is becoming a serious threat to global health.

You can take a deeper dive into these specific chemicals here.

BONUS: Perc (dry cleaning)

Your clothing may or may not contain perchloroethylene (aka “perc”)… It depends on if you take your clothes to the dry cleaners or not.

Perc is a known carcinogen and some states are starting to phase it out of dry cleaning and require dry cleaning companies to transition to a safer alternative. You can learn more perc and less toxic dry cleaning methods here.

What you can do:

- If you need to use a dry cleaner, look for one in your area that uses “wet cleaning” (which is the best option), GreenEarth® dry cleaning, liquid carbon dioxide cleaning, or hydrocarbon dry cleaning.

- Put more time in between your trips to the dry cleaner by spot cleaning your clothes and/or spraying them with Force of Nature or diluted vodka in between washes.

- Skip the dry cleaners altogether by hand-washing your clothing or using a steam cleaner at home.

Ways to Minimize the Toxic Chemicals in Your Wardrobe

We’ve included many tips above, but here’s a quick list of things you can do to decrease your toxic exposure from your wardrobe:

- Wash your new clothes before wearing them for the first time.

- Use non-toxic laundry detergent.

- And skip the dryer sheets (or at least use one of these alternatives).

- Avoid fast fashion when possible.

- Opt for more natural, organic, and plant-based clothing, as they are less likely to contain various toxic chemicals.

- Implement more undyed and/or neutral-colored garments into your wardrobe.

- Look for third-party certifications such as GOTS, OEKO-TEX, and bluesign.

- Try to avoid “performance” fabrics like “antibacterial,” “moisture-wicking,” “UV-protecting,” etc.

- Change out of sweaty clothes after a workout.

- Avoid dry cleaning your clothes when you can.

- Transition your wardrobe to natural and non-toxic clothing slowly. As you wear out article of clothing, replace them with healthier garments.

- If you have organic bed sheets… sleep naked! It means less time with potentially toxic fabrics against your skin.

Where to Find Non-Toxic Clothing Brands

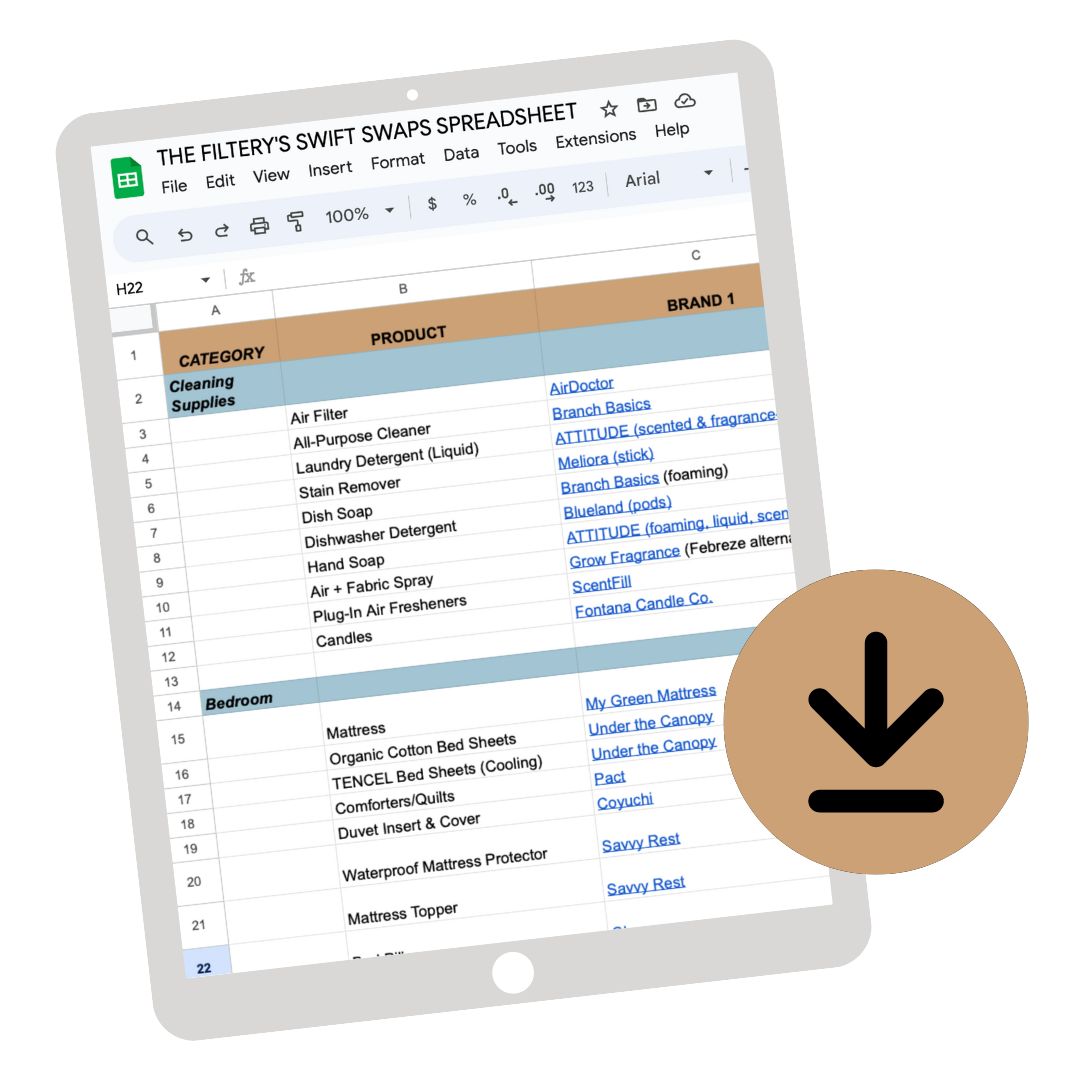

Check the Wardrobe section of The Filtery, where we’ve got lots of guides to non-toxic and organic clothing in various categories.

To get more pointers (and more) delivered to your inbox each week, sign up for Filtered Friday.