There are quite a few myths and misunderstandings out there about environmental toxins and non-toxic living.

Many of them are very understandable. Others are manufactured on purpose by industries that want consumers to be confused because it’s profitable. Many misconceptions are a result of a lack of regulation around chemicals and labeling.

In this article, we’re talking about the most common myths and misconceptions in the hopes of clearing some things up and leaving you more empowered and confident on your journey toward low-tox living.

Table of Contents

- #1: Chemicals are tested for safety before they hit the market.

- #2: The dose makes the poison.

- #3: “I’ve been using X product my whole life and I’m fine.”

- #4: If it’s natural, it’s healthy. If it’s synthetic, it’s not healthy.

- #5: If it’s long or hard to pronounce, it’s toxic.

- #6: “My doctor said it’s fine, so it’s fine.”

- #7: “BPA-Free” or “Phthalate-Free” or “Whatever-Free” means it’s safe.

- #8: Shopping organic/non-toxic is more expensive.

- #9: “Everything is toxic, so I shouldn’t even bother.”

- #10: You can live a 100% non-toxic lifestyle.

#1: Chemicals are tested for safety before they hit the market.

This is one of the most common (and perhaps one of the most important) misconceptions about chemicals, ingredients, and materials. I hear or read people say things like, “If these products were so bad, they wouldn’t be allowed on the shelves!”

Nope. In fact, less than 1% of the chemicals on the market in the U.S. have been tested for human safety.

There are actually several counterpoints to this argument, so let’s break them down one at a time:

- Chemicals are assumed safe until proven otherwise.

This is mostly because of the way the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) was set up. Legally, it takes an “innocent until proven guilty” approach to chemicals; the EPA is not actually allowed to regulate a chemical until after it has been determined to be harmful. (And by that time, it has usually been flowing into our environment for decades. This has been the case with DDT, PCBs, PFAS, lead, etc.)

Plus, back when the TSCA was first put into place in 1976-77, about 62,000 chemicals were “grandfathered” into approval without being tested. (Even asbestos, which kills ~10,000 people per year in the U.S. alone, was grandfathered in!)

2. Chemicals are generally either not tested at all, or only tested for short term effects (such as a skin rash), not longterm effects (such as cancer or hormone disruption).

Most companies will do a minimal amount of testing (usually ~3 months worth) before releasing chemicals or finished products, but it’s almost always to make sure it won’t cause any short-term reactions. For example, a cosmetic company may do testing to make sure a product won’t cause a skin rash.

However, they almost never look at potential long-term effects (like cancer), nor do they look at slight alterations in things like insulin resistance or immune response, which can lead to more extreme effects down the road. They’re looking for immediate and visible effects—that’s it.

3. Even when chemicals are researched for more longterm effects, companies cannot be trusted to be honest about the risks their chemicals may pose.

When testing actually does take place, it’s generally done in-house by the companies themselves, not by government regulators or neutral third-parties. There are almost never any outside organizations holding them to account (unless the company chooses to enlist the help of a third-party lab or certification program).

To make matters worse, there’s a pretty shameful track record of that research getting buried. For example, DuPont knew from their own research that PFAS were toxic and lied and hid it for years. Monsanto knew PCBs were toxic and did the same time. Tobacco companies knew smoking was harmful and lied about that for decades as well.

Chemical manufactures have proven themselves untrustworthy over and over again—even when they actually do test their products.

4. “Safe” levels can be inadequate for the real world.

The last thing to note on this point (for now) is that even when a certain amount of a chemical is deemed “safe” through scientific data, that safety doesn’t always translate to the real world. These “safe” levels set by regulators often look at a chemical in a vacuum, as if that one chemical from that one product is all a person is being exposed to in a day.

But we know that isn’t how it works in the real world. We are exposed to hundreds of products and chemicals each and every day—from our furniture, to our personal care products, to the materials we work with at our jobs, to the toxicants in our air and water, and more… All of these cumulative and low-dose exposures can add up, and the data that’s used to determine “safe levels” of chemicals doesn’t take that into consideration.

#2: The dose makes the poison.

Sometimes this is true, but sometimes it’s not.

“The dose makes the poison” generally means that when someone is exposed to MORE of a substance, that substance will have MORE of an effect, and if they are exposed to LESS of a substance, it will have LESS of an effect.

While this is certainly true of a lot of different chemicals, there are some types of chemicals (specifically, endocrine disruptors) that can actually have larger effects at lower doses. This is in large part because of how the body’s hormonal systems work, how sensitive those systems are, and how small changes can lead to profound impacts down the road (like a hormonal butterfly effect).

#3: “I’ve been using X product my whole life and I’m fine.”

There are two main pushbacks to this objection—one has to do with the individual and one has to do with the collective.

First is the issue of epigenetics. If you aren’t already familiar, epigenetics is basically the way in which one’s environment influences their genes. We tend to think of a lot of illnesses in terms of being *just* genetic or *just* environmental, but in reality, that’s not how things work most of the time.

Someone may have a genetic pre-disposition to a certain disease, but whether or not that disease actually ever shows up depends on the environment they live in. “Environment” can mean anything from air pollution, to smoking, to a single traumatic event, to longterm stress, and more. These environmental factors can essentially “trigger” one’s genes toward disease manifestation.

In the same way, some people are not predisposed toward certain diseases and they can even have certain genes or life circumstances that counterbalance potentially harmful environmental exposures. These are the people who can usually say “I’ve been using X product my whole life and I’m fine.”

Think about how some people smoke cigarettes their whole lives and never end up with lung cancer. Just because that one individual does not get lung cancer from smoking does not mean smoking doesn’t increase the overall chances of getting lung cancer for the general population.

Additionally, there are a lot of people with chronic conditions of various types (cancer, autoimmunity, asthma, eczema, autism, multiple chemical sensitivity, etc.) whose conditions make them more sensitive to chemicals. So just because you might be “fine” doesn’t mean other individuals don’t have good reason to avoid toxins in their life.

Another thing to consider on this point is that you could technically revise the statement to “I’ve been using X product my whole life and I’m fine so far.” Just because an individual hasn’t been affected (or noticed any affects) of environmental toxicants so far doesn’t necessarily mean anything about the future.

This is important to keep in mind because for your average, everyday consumer, the toxicant exposures we’re talking about are chronic, low-dose exposures that happen over long periods of time, and their effects can take time, too. For example, some research indicates that in-utero exposure to certain hormone-disrupting chemicals may not show up until decades later.

(I don’t say this to try and scare anyone, but simply to make a point about the nature of low-dose, longterm exposure.)

Now let’s talk about the second main pushback to this objection, which has to do with communities and our ecosystem as a whole.

Let’s say, for the sake of this argument, that a finished product truly is non-toxic and safe for an individual to use. Great. But what if we back up and consider the way in which that product was made? What chemicals and processes were involved? Where was it made, and who made it?

Time after time, we’ve seen communities poisoned by chemical companies during and after manufacturing. Cancer Alley in Louisiana. Chemical Valley in Ontario. I could go on and on.

Factory workers are exposed to high levels of toxicants (often while being lied to about the risk) and end up with all kinds of diseases and disorders. Toxic waste is dumped into waterways, where it ends up in the tap water that the whole community drinks. Then that community ends up with higher than average rates of cancer, birth defects, miscarriage, infertility, and more. This can happen anywhere, but it happens disproportionately to people lower socioeconomic status and people of color, both in America and around the world.

Then of course, if we zoom out even further, we have to consider the impacts these chemicals have on our entire ecosystem as a whole. Even if one person is “fine” when they use a certain chemical doesn’t mean that our future generations will be “fine” with the longterm consequences of these chemicals being spread into the deepest parts of the ocean and the most remote parts of Antarctica.

Finally, I have a third pushback to the “But I’m fine” argument, and this one is more conceptual. The question is: what do you really mean by “I’m fine,” anyway?

Sadly, it seems like a lot of the people in our modern world are just kind of “getting by” with their head above water in terms of their health and happiness. So many people struggle with managing their mental, physical, and relational health. Around 1 in 5 Americans are taking psychiatric drugs of some kind. The number of people with chronic disease has been on the rise for a while now. The life expectancy in the U.S. is decreasing.

None of this exactly communicates that we’re “fine.”

Of course, there are a lot of reasons for these trends, many of them sociological, cultural, and political. Exposure to environmental toxicants is just one piece of the puzzle here—but it is one piece. Toxic chemicals are associated with pretty much all chronic conditions (both mental and physical) in one way or another, as well as early death.

Again, when we zoom out and look at the big picture, the “I’m fine” argument may not really hold up…

#4: If it’s natural, it’s healthy. If it’s synthetic, it’s not healthy.

Not necessarily. Asbestos, lead, mercury, certain kinds of mushrooms—these are all examples of naturally-occurring substances that are very toxic.

Similarly, there are plenty of man-made synthetic substances that are safe.

There is gray area here, and whether or not something is safe or healthy varies by ingredient and the way in which it was sourced and processed.

One might argue that in general, natural ingredients are more likely to be healthier because they tend to be less processed and not petroleum-derived. But just because something is natural does not automatically mean it’s non-toxic or healthy, and just because an ingredient is synthetic doesn’t automatically mean it’s toxic or bad.

#5: If it’s long or hard to pronounce, it’s toxic.

This one kind of goes along with the previous misconception. I’ve heard people say that if you can’t pronounce the ingredients on the label, you shouldn’t buy it.

But the number of letters in an ingredient and whether or not you can pronounce something doesn’t inherently mean anything about the safety of a chemical. For example, how many people know what vaccinium angustifolium leaf extract means? (It’s just the official name for blueberry extract.)

I do, however, think it’s very unfortunate that so many of the ingredients on labels (both natural and synthetic) are so long and hard to understand. I think this is one of the biggest barriers to entry when it comes to swapping out toxic products for safer alternatives… Who has the time to research all of those chemicals and try to memorize them?!

So although the length of a chemical or how difficult it is to pronounce doesn’t automatically mean anything about its safety, I do think it could be beneficial if we could find a way to make ingredient labels generally easier to understand across the board.

#6: “My doctor said it’s fine, so it’s fine.”

Unfortunately, for all of their time spent in medical school, Western doctors get very little training on environmental toxins. Although it varies by school and concentration, the statistic that’s often stated is that MDs get an average of seven hours of training on environmental chemicals.

Similarly, doctors only get about 20 hours of education on nutrition. This is kind of wild considering how much impact food can have on one’s short and longterm health! But the conventional Western medicine model focuses more on treatment rather than prevention.

As mentioned earlier, incidences of all kinds of chronic illnesses (including asthma, infertility, autoimmunity, cancer, diabetes, Alzheimer’s, depression, gut dysbiosis, and more) are on the rise, and environmental toxins are linked to all of these throughout the scientific literature. Although toxic chemicals are not the only cause, they are a very important piece of the sickness/health puzzle.

Because of this, doctors should have more education on environmental toxins if they are to truly help their patients, and this seems to be slowly starting to change. For example, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine and the CDC have recently released reports advising clinicians and patients about PFAS chemicals.

On a related note, chemists in the U.S. also aren’t required to take any courses in toxicology. That means the chemists at DuPont, 3M, P&G, and the rest of the companies that are making all of these new chemicals aren’t educated in how to determine whether or not the chemicals they’re making are harmful.

#7: “BPA-Free” or “Phthalate-Free” or “Whatever-Free” means it’s safe.

Nowadays, you see these “________-Free” labels on products all the time. So do these labels mean the product is really safe and totally non-toxic?

Frustratingly, the answer is sometimes yes and sometimes no.

Here are some things to keep in mind for this one:

#1. For the most part, no one is regulating these claims. Companies put them on their products because they choose to and because of consumer demand. There are no standards they have to meet or prove in order to put these kinds of labels on their products. There is no one holding them accountable. (The exception is if the label is a true third party certification such as USDA Organic or Certified Gluten Free. These third party verification systems do have standards products have to meet, but they’re mostly voluntary.)

#2. It raises the issue of what we call “regrettable substitutions.” This is basically when a toxic substance is replaced by a different substance which is actually just as bad (or maybe even worse!). The perfect example of this is BPA. When it was discovered that BPA was toxic and it started to be banned, many companies just replaced it with its “chemical cousin,” BPS. Even though BPS is just as bad as BPA, companies could technically put a “BPA-Free” label on their products even though the products weren’t actually any safer!

(P.S. One way around this is to look for labels that indicate a product is free from entire groups of chemicals, as opposed to just one chemical in that group. So for example, you could look for a label that says “Bipshenol-Free” instead of just “BPA-Free,” or “PFAS-Free” instead of just “PFOA-Free.”)

#3. These labels don’t always take into consideration the other ingredients or materials used. For example, if a shampoo bottle says “Paraben-Free” on it, that’s great, but it doesn’t mean anything about whether or not there are phthalates (which is a different kind of endocrine disrupting chemical). That’s why whenever you look for these kinds of labels, you may want to look for many of them as opposed to just one or two.

While these labels can definitely be helpful, they are also used to greenwash products and confuse consumers, so they should usually be taken with a grain of salt.

#8: Shopping organic/non-toxic is more expensive.

This is definitely a valid concern. Non-toxic products (along with clean air and water) should be accessible to everyone, regardless of socioeconomic status and other demographics. This has been and is still a problem; lower income communities are not only more likely to breathe more polluted air and drink more polluted water, but they also tend to have less access to things like healthy and organic food and other products.

Sometimes buying organic and non-toxic products is more expensive and sometimes it isn’t. It often varies by the type of product and how you buy it (for example, from the grocery store versus from a community garden).

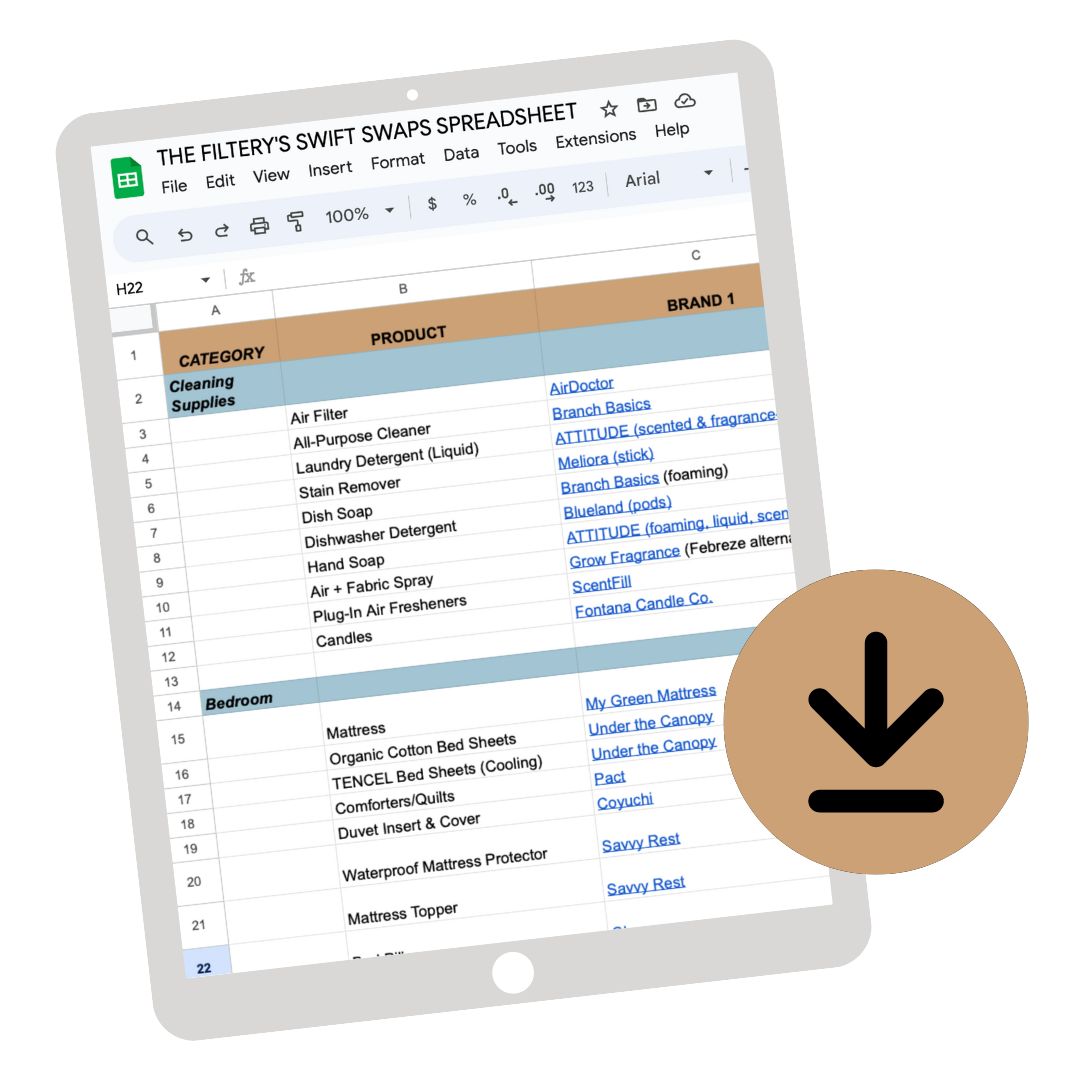

One easy way to save money while transitioning to a low-tox lifestyle is by simply buying less products. For example, many people have ten different cleaners in their home—an all-purpose, bathroom, kitchen, laundry, wood, floor, toilet, etc. etc… All of those different products add up!

But if you switch to a truly all-purpose product (like Branch Basics, for example), you can not only save some money but also the time and effort that goes into researching the ingredients in all of those different formulations (and it’s less plastic packaging, too!).

Natural DIY recipes are another way to save money, too, if that’s your thing.

Regardless, we all have different capacities, and no one should ever be shamed or blamed for not being able to afford organic or eco-friendly products. We all must do the best we can, according to our own capacities.

#9: “Everything is toxic, so I shouldn’t even bother.”

I definitely understand the frustration and cynicism that can come along with non-toxic living. Once you start down the path, you start to see how many toxins we’re surrounded by every day, and it can be very discouraging.

Of course, many people don’t have much of a choice… Those who struggle with things like infertility, asthma, multiple chemical sensitivity, and other conditions have to decrease environmental toxicants for the sake of their wellbeing.

But you already know that I personally believe there is value in everyone else working towards a low-tox lifestyle as well, both as a preventative measure on an individual basis as well as for the holistic health of our collective ecosystems.

I definitely believe we should take it one step at a time in order to reduce overwhelm as much as possible. I don’t usually recommend anyone tries to overhaul their life overnight—it’s not sustainable for the longterm and it can easily lead to burning out and giving up.

To help you get started, you can sign up to download my guide to 25 (easy & low-cost) things you can do to decrease environmental toxins in your life:

#10: You can live a 100% non-toxic lifestyle.

No. I’m sorry. There are a lot of toxins we can’t avoid. There are all kinds of toxicants in the air that we can’t help but breathe in. There is stuff in the water that we can’t always filter out (like if we ever want to eat at a restaurant). We may not always be able to 100% avoid plastic simply because of the way our society is set up. PFAS contamination is everywhere—even in products where it wasn’t added intentionally.

In my opinion, this is why it’s important to do what we can control. And although that might not be everything, there is a LOT we can do! We can stop using things like candles, air freshener sprays, and nail polish. (Or at least use non-toxic alternatives.) We can switch to non-toxic cleaning products. We can filter our indoor air and water. We can use glass instead of plastic to store our food. As the more expensive products in our home (like mattresses) start to wear down and need replaced, we can start to replace them with healthier alternatives.

All of these things can really add up and can make a big difference for the present and future health of you, your family, and the planet.

I hope this helps to provide some clarity around some of the myths and misunderstandings surrounding environmental toxins and non-toxic living. If there are any misconceptions I missed, feel free to let me know in the comments below. And if you’d like some more tips & tricks (and other fun stuff) delivered to your inbox once a week, be sure to sign up for Filtered Fridays.